Dwellings are places to dwell, habitations to inhabit. The two words, ‘dwellings’ and ‘habitations,’ mean the same thing. Accordingly, I could have made the subtitle to this piece “Crafting Habits for Inhabiting Habitations.” As a matter of fact, that — “Crafting Habits for Inhabiting Habitations” — was one version of the title for this post that I at one point crafted for it.

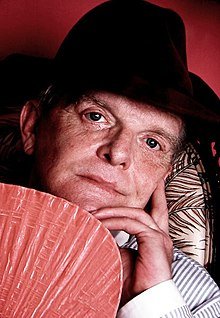

Crafting and then recrafting titles, as well as everything else that I write — just as I have been busy for quite a while writing, then rewriting again and again, this first section of this very post — have been habitual to me as long as I can remember. As I once heard Truman Capote say to Johnny Carson on one of the latter’s shows, “Good writing is re-writing.” In substance, I learned that when I first learned to write.

I so learned not by listening to schoolteachers of writing or the like, but by attentively listening to what the words I wrote themselves said. After all, it is only by such attentive listening to what words themselves tell us that we can learn any craft at all, whether those be crafts for building dwellings[1] or crafts for dwelling in dwellings already built. That includes the most basic of all such crafts for inhabiting dwellings: the craft of attentive listening itself, or, to put the same thing just a bit differently, the craft of genuinely asking to hear.

Truman Capote in 1989 (picture by John Mitchell)

* * *

Ask and it will be given to you; seek and you will find; knock and the door will be opened to you. For everyone who asks receives; the one who seeks finds; and to the one who knocks, the door will be opened.

— Matthew 7:7-8 (NIV)

To ask is no more and no less than to open oneself to receive. What is more, it is only if we truly do ask — that is, truly do open ourselves to receive — that we ever truly can and do receive. Only in so asking can we ever acquire any of the great gifts that are, in fact, constantly given to us to receive.

One need not be a Christian to have received that message. One only needs to have good manners, which is to say be well bred.

* * *

Example is notoriously more potent than precept. Good manners come, as we say, from good breeding or rather are good breeding; and breeding is acquired by habitual action, in response to habitual stimuli, not by conveying information. — John Dewey[2]

Learning always to ask questions — that is, learning always to hold oneself open to receive the gifts one is given — is the best of all good manners to which anyone can ever be bred, which is itself the very greatest gift one can ever receive. To receive that greatest of all gifts, to be bred with that best of all good manners, itself requires that one be fortunate enough to be born into a community rich in examples of those who have themselves already been so richly gifted, so well bred.

To have received such good breeding and such a great gift is to have been taught how to learn, which is the most important thing anyone can ever teach another. One teaches that lesson not by lecturing, scolding, or imparting information, but by being a living example of someone who has already learned it.

* * *

The spoken word is a gesture, and its meaning, a world. — Maurice Merleau-Ponty[3]

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.

— John 1:1 (NIV)

The common word ‘acquire,’ heard with an ear tuned to the etymological roots of the word ‘acquire,’ means to receive an answer to a “query,” that is, a question.

If one has acquired, by good breeding, the well-mannered habit of always listening attentively to whatever one is told, then what one will hear in every word one has ever been given to hear no less than a whole world.

To borrow a line I first heard coming from the mouth of Yul Brynner, playing Ramses, the Pharoah of ancient Egypt in the old Cecil B. DeMille movie The Ten Commandments when I saw that film with my parents when I was a child:

“So let it be written, so let it be done.”

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

[1] Including, as I discussed already in my preceding post — “Dwelling-Crafts I: Crafts for Crafting Dwellings,” published on 1/22/24 and available in the “Archive” at the top of this blogsite — that most essential of all dwelling-building crafts: thinking.

[2] From Democracy and Education, “Chapter 2. Education as a Social Function,” section “3. The Social Medium as Educative.”

[3] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, translated by Colin Smith (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962), p. 184.